There’s so much consternation about the Mexican border today. Here’s a story about the survey that established the border in 1849-1850. Of course, planthunters went on the expedition. Really? Do you think this post would be here if it didn’t include flowers?

Under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, ending the Mexican-American War, the U.S. purchased 1.2 million miles of Mexico – Texas, New Mexico, Nevada, Arizona and California – for $15 million. The Treaty created a joint commission to survey and establish the boundary. Botanist-planthunter C.C. Parry (1823-1890) was appointed one of four of the botanists on the Boundary Survey. Each collected plants in separate locations.

Not all went well with the survey.

There was the California gold rush. The crew – nearly 50 surveyors, astronomers, botanists, interpreters, draftsmen, cook, doctor, to name a few, plus 150 military escort and all their equipment, wagons, horses and mules – was to meet their Mexican counterpart in San Diego on May 31, 1849. Sailing to the Atlantic side of Panama, crossing the 75 mile isthmus overland, then sailing north on another ship on the Pacific side was the usual route from the East to California. The crush of 4000 gold seekers in Panama waiting for ships stranded the members of the Survey in Panama for two months. The Mexican Survey crew arrived even later.

The human deluge caused hyperinflation in California. Prices skyrocketed for the Survey’s supplies. The cost of soldiers’ rations increased nearly eight-fold, from $.20 to $1.50 per day. Worse, the government refused to appropriate money for the Survey, misrepresented that fact and when it did award money, the bureaucrats did not forward it. The government protested drafts made on its account leaving the Survey penniless and without credit. (Sound like a furlough?) After not being paid for 18 months many men abandoned the Survey, lured by the glow of gold not far to the north. Parry stayed.

From September to December 1849 Parry joined part of the expedition on the farthest and most dangerous route – to map the junction of the Gila and Colorado Rivers. Their wagon train, Company “A” of the First Dragoons, infantrymen, horses, and mules quartered at ranches and Indian settlements. At Vallecito, the last oasis before crossing the desert, “barren and desolate in the extreme,” it reached 104°. They crossed the desert by night. At the next water supply, Carrizo Creek, they found dead animals in and near the salty water. After marching on without water for 18 hours they stopped and desperately dug for water with no success. Unexpectedly, menacing gray clouds appeared in the eastern sky. A maelstrom of sand hit with gale force ripping the canvas tops off the wagons. Rain poured down, turning to hail and then floods. Three weeks after leaving San Diego they established a camp, home for three months, at the confluence of the Gila and Colorado Rivers. Parry collected plants and observed the Yuma Indians cultivating corn, beans, melons, and pumpkins in the “oppressively sultry” heat, frequently “100° in the shade.”

President Polk, a lame duck, had appointed the first commissioner, Weller, shortly before the end of Polk’s term. Zachary Taylor fired Weller and offered the job to J.C. Fremont. Fremont, then occupied with his gold mine, dallied and finally declined the appointment. With no U.S. commissioner the Survey could not proceed. The Mexicans and remaining Americans met in February 1850 and resolved to suspend the Survey and meet at El Paso in November, hoping a new commissioner would be in place.

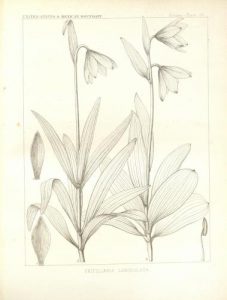

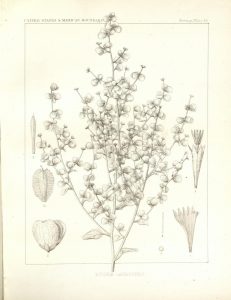

Dicoria canescens, Desert twinbugs collected on the Mexican Boundary Expedition

Parry returned to San Diego, kept busy collecting plants and then rejoined the survey in El Paso. He accompanied an exploring party west of El Paso to the Pima settlements on the Gila River. Parry also accompanied several surveying parties on the line of the Rio Grande south of El Paso and the river below Presidio del Norte.

Parry authored the introduction to Dr. John Torrey’s Botany detailing the area’s ecosystems. The Report of the United States and Mexican Boundary Survey received rave reviews (“it must be ranked as the most important publication of the kind that has ever appeared.”) The narrative of the Survey including illustrations of the scenery is in volume 1. The plant, reptile, fish, mammal and bird information and illustrations are in volume 2. You can find it at: https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/95705#page/1/mode/1up